ASTMH 2017: Symposium 121 “School-Based Malaria Interventions: Impact on Health and Transmission”

Published: 10/12/2018

This report is brought to you by the MESA Correspondents Krystal Birungi, and Krijn Paaijmans.

THEMES: THEMES: Impact of Interventions | Vulnerable Populations

MESA Correspondents bring you cutting-edge coverage from the 66th ASTMH Annual Meeting

Symposium 121: “School-Based Malaria Interventions: Impact on Health and Transmission”

Session 121 of the 66th Annual Meeting focused on School-Based Malaria Interventions and their impact on health and transmission. All the speakers agreed that school-age children are a demographic group most affected by malaria infections and that contribute the most to malaria transmission. They called for targeted malaria interventions within this group as a way to reduce malaria transmission in the community, and encouraged scientific discussion on how this can be advanced.

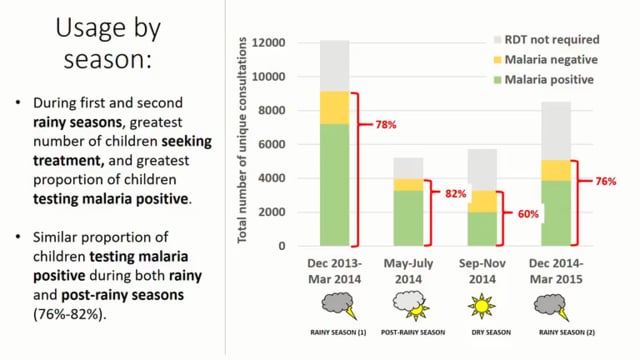

Don Mathanga from the College of Medicine of the University of Malawi in Blantyre, talked about malaria in school-age children and its impact on health and education. He highlighted that school-age children are a group that uses interventions such as long lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) much less compared to other age groups and have limited access to treatment. He presented the results from a cluster-randomised trial in 58 primary schools in Malawi that aimed to evaluate the impact of school-based malaria case management on absenteeism, well-being, health, and education. The intervention involved training teachers to use rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and treat malaria-infected children using a ‘learner treatment kit’. Even though the results showed no significant impact on daily attendance or in malaria parasitemia, anemia, and educational performance, they showed significant differences in the primary point of access to care: In the intervention schools fewer children reported that shops and health centres were their primary point of access to care for a febrile event compared to children in schools in the control group. These results add value to the idea of improving access to treatment in this age group through schools.

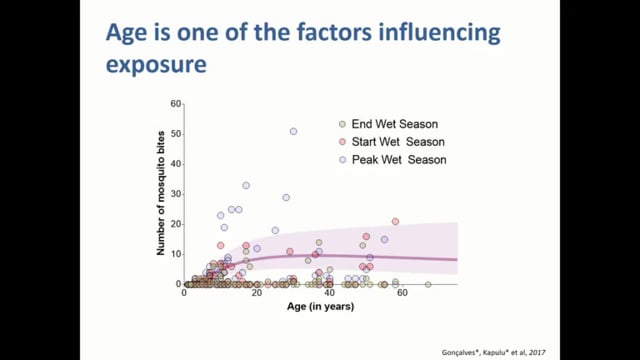

Bronner Gonçalves from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, presented recent transmission studies in Burkina Faso and reviewed the evidence supporting the significant role of school-age children in malaria transmission. He presented data from a study that aimed to quantify age-specific infectiousness prevalence and mosquito exposure by using membrane feeding infectivity surveys. The results showed that school-age children (5-15 years old) had the highest infectiousness prevalence, but since adults had higher mosquito exposure, the result was that school-age children and adults contributed almost equally to onward transmission in the study area.

Catherine Maiteki-Sebuguzi from the Uganda National Malaria Control Programme presented the results from the START-IPT trial, which aimed to evaluate the impact of IPT (intermittent preventive treatment) with an ACT (artemisinin combination therapy) in schoolchildren on malaria transmission indicators at the community level. In the schoolchildren in intervention schools, there was a lower proportion of RDT positive and microscopy positive results, together with less history of fever. Parasite prevalence at the community level was not statistically significant between the control and intervention clusters, but a positive trend was seen. Catherine concluded that the results suggest that IPT for schoolchildren benefited the individual children and may reduce malaria transmission within the community. She also shared some of the challenges faced by this form of intervention, such as community sensitization and recruitment through schools; as well as some questions for future studies, such as how to achieve high coverage rates or how to integrate the intervention with other school-based programmes.

Lauren M. Cohee from the University of Maryland School of Medicine in the United States, presented the results of a systematic review of school-based malaria treatment interventions and considerations of key factors in designing future interventions. They performed pooled analyses of data from 12 randomised trials assessing the effect of antimalarial treatment to “asymptomatic” school-age children across Africa. The evidence suggests that treating asymptomatic schoolchildren decreases the prevalence of malaria infection and anemia, with the greatest effects seen with ACTs. The evidence also suggests some potential to decrease malaria transmission and improve educational outcomes, but more studies are needed since educational outcomes are difficult to measure. However, there are remaining questions, such as if treating “asymptomatic” school-age children is appropriate for all transmission settings or if there’s a need to tailor the treatment or age groups based on the epidemiological setting.

This blog was written by Krystal Birungi and Krijn Paaijmans with editorial support from the MESA team. It is cross-posted on Malaria World. The videos have been made available to all through a collaboration between ASTMH, AV Images, and MESA.

Published: 10/12/2018

This report is brought to you by the MESA Correspondents Krystal Birungi, and Krijn Paaijmans.